🤔 What is Shell or Terminal ?

The terms "shell" and "terminal" are closely related but refer to different concepts in the context of computing.

Shell:

A shell is a command-line interpreter or interface that interprets and executes the commands entered by a user.

It's a program that provides the user with a way to interact with the operating system by accepting commands and executing them.

The shell interprets the commands and communicates with the operating system to perform various tasks.

Examples of shells include Bash, PowerShell, Zsh, and others.

Terminal:

A terminal, on the other hand, is a program or device that provides a text-based interface for the user to interact with the computer.

It's a software application that allows the user to input commands and receive text-based output.

The terminal hosts the shell. When you open a terminal, you are typically presented with a command prompt where you can enter commands.

Terminal emulators, such as GNOME Terminal, iTerm2, or Command Prompt, are applications that provide the actual terminal interface on a computer.

In essence, the terminal is the environment in which you interact with the shell. When you open a terminal, you're given a command prompt where you can type commands, and those commands are interpreted and executed by the shell. The shell, in turn, communicates with the operating system to carry out the requested tasks.

In summary, the shell is the command interpreter, while the terminal is the program or interface that hosts the shell, providing a way for users to enter commands and receive text-based output. The two work together to enable command-line interactions with the operating system.

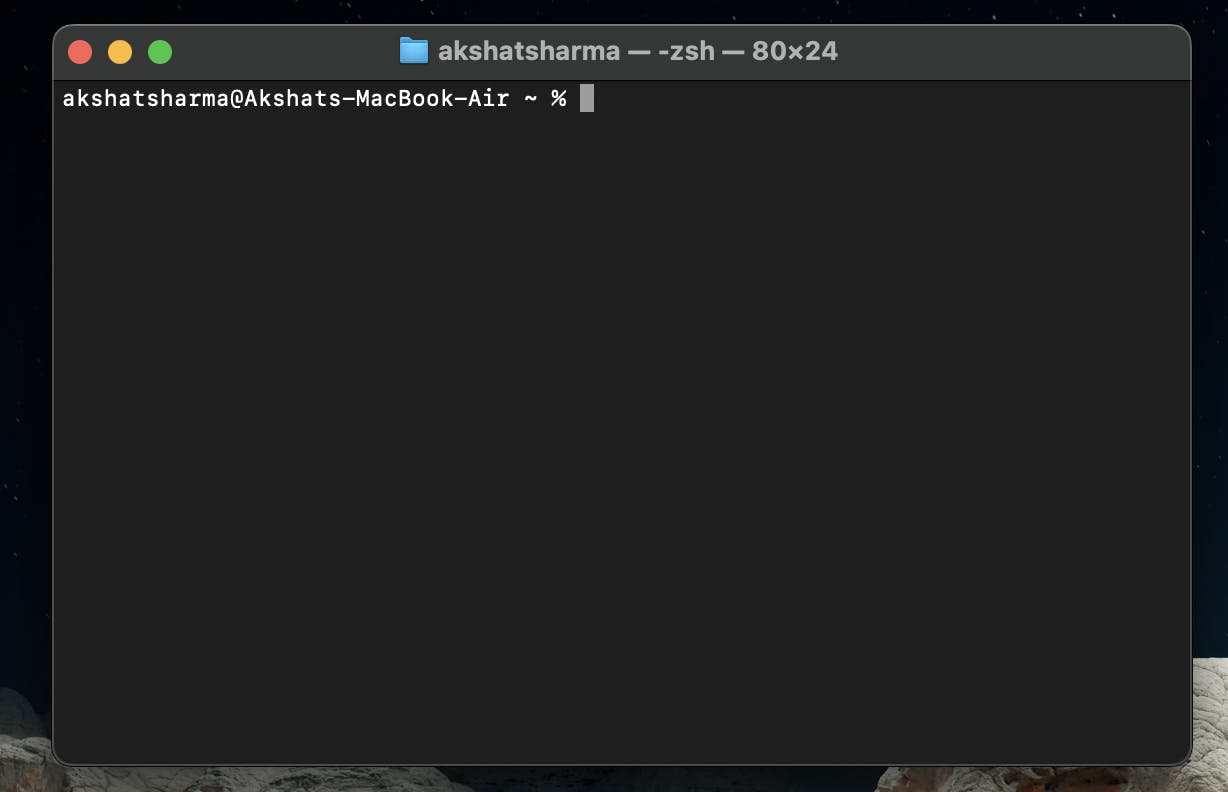

💪🏽 Ok Now I opened the terminal ... this is what I see.

What you're seeing in the terminal prompt on your MacBook is called the command prompt. Let's break down the information it provides:

akshatsharma: This is the username of the current user who is logged into the system. In this case, the username is "akshatsharma."

@Akshats-MacBook-Air: This part usually represents the name of the computer or host. In your case, it's "Akshats-MacBook-Air."

~: This tilde symbol represents the current working directory. In Unix-like systems (including macOS), the tilde (

~) is a shorthand for the user's home directory. So,~means you are currently in the home directory of the user "akshatsharma."%: The percent sign is the command prompt itself. It indicates that the terminal is ready for you to enter a command.

So, the whole prompt "akshatsharma@Akshats-MacBook-Air ~ %" is telling you that you are currently logged in as the user "akshatsharma," on a computer named "Akshats-MacBook-Air," and you are in the home directory, ready to enter a command.

Feel free to start typing commands after the % symbol to interact with your Mac using the terminal. For example, you can use commands like ls to list files, cd to change directories, and more.

🛜 I got few commands online but how does the computer know what each command means ?

When you type a command like ls in the terminal, the shell knows what it means through a process called command resolution. Here's a simplified explanation of how it works:

Shell Built-in Commands:

The shell has a set of built-in commands that it recognizes directly. These commands are part of the shell itself.

Examples of built-in commands include

cd(change directory),echo(print to the screen), andpwd(print working directory).

External Commands:

If the entered command is not a built-in one, the shell looks for an external program or executable file with a name that matches the command.

The directories where the shell searches for these programs are specified in the system's PATH environment variable.

PATH Environment Variable:

The PATH variable (an Environment Variable) is a list of directories separated by colons (

:). It tells the shell where to look for executable files when a command is entered.For example, if you type

ls, the shell checks each directory listed in the PATH to find an executable file namedls.

What is Environment Variable ? -> Environment variables are key-value pairs that store information about the environment in which a process runs. They are used by the operating system and applications to configure behavior, set preferences, and share information. Here are some common types of environment variables:System Environment Variables:These are global variables that apply to the entire operating system. They are set by the operating system during startup and are accessible by all processes. Examples include variables specifying system paths, default locales, and system-wide settings.

User Environment Variables:These variables are specific to a user's session. They are set or modified by the user and are applicable only to processes running in that user's context. Examples include user-specific paths, language preferences, and custom settings.

Application-Specific Environment Variables:Many applications use environment variables to customize their behavior. These variables are specific to the application and influence how it operates. Examples include configuration paths, debug settings, and license information.

Shell Environment Variables:Shells, such as Bash, PowerShell, or Zsh, use environment variables to configure their behavior and provide information about the user's environment. Examples include PATH (specifying directories to search for executable files), HOME (user's home directory), and PS1 (shell prompt).

Process-Specific Environment Variables:Each running process can have its own set of environment variables. These variables may be inherited from the parent process but can also be modified independently. They are specific to the context of the running application.

Temporary Environment Variables:Some environment variables are set temporarily for the duration of a specific command or script. These variables are often used to override default settings for a short period. For example, setting LANG=C temporarily changes the language environment for a command.

Built-in Environment Variables:Some environment variables are predefined by the operating system or the application runtime. Examples include PWD (current working directory), USER (current user's username), and HOME (current user's home directory).

Execution:

- Once the shell finds the executable file (in the case of

ls, it's typically located in/bin), it launches that program, passing any additional arguments you provided.

- Once the shell finds the executable file (in the case of

So, when you type ls, the shell knows what it means because it either recognizes it as a built-in command or finds an external executable file named ls in one of the directories specified in the PATH.

This system allows the shell to understand and execute a wide variety of commands, whether they are built into the shell or external programs installed on your system. It's a key mechanism that makes the command-line interface flexible and extensible.

In Linux, files and directories that start with a dot (.) are called "dot files" or "hidden files." The dot at the beginning of the filename indicates that the file is hidden from normal directory listings. This convention is used to store configuration files and settings for various applications, preventing them from cluttering the user's view when listing files in a directory.

For example, common dotfiles include configuration files like

.bashrcfor the Bash shell,.gitignorefor Git version control, and.configfor storing application-specific configuration files. To view hidden files in a directory listing, you can use the-aoption with thels

🧐So the Command 'ls' itself is an executable file ?

Yes, ls is an executable file, and it's a command-line utility used to list files and directories. The ls command is typically found on Unix-like operating systems, including Linux and macOS.

As for the language in which ls is written, it is typically written in the C programming language. Many core utilities and commands on Unix-like systems are implemented in C for several reasons:

Efficiency: C is a low-level language that allows for efficient system-level programming. It provides direct access to system resources and is well-suited for tasks like file manipulation and system calls.

Portability: Code written in C is highly portable across different platforms. Since Unix-like systems come in various flavors (Linux, macOS, BSD, etc.), having portable code allows these utilities to work on different Unix-like systems without major modifications.

Legacy: Many of these utilities, including

ls, have a long history dating back to the early development of Unix. C has been a prevalent language in Unix development since its inception, contributing to the tradition of using C for these tools.

Here's a basic, conceptual example of how a simple ls command might be implemented in C

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <dirent.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

// Open the current directory

DIR *directory = opendir(".");

if (directory == NULL) {

perror("Error opening directory");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Read directory entries

struct dirent *entry;

while ((entry = readdir(directory)) != NULL) {

printf("%s\n", entry->d_name);

}

// Close the directory

closedir(directory);

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

🤯So the 'Shell' Compiles these Codes ?

No, the shell doesn't directly interpret the C code for utilities like ls. Instead, the compilation process translates the human-readable C code into machine-executable code.

Writing Code: A programmer writes C code for the

lsutility, including the logic for listing files and directories.Compilation: The C code is then compiled using a C compiler (like GCC or Clang). The compiler translates the high-level C code into machine code (binary code) that the computer's hardware can execute. This command compiles the C code in the file

ls.cand generates an executable file namedls.gcc ls.c -o lsExecutable File: The result is an executable file (

lsin this case) that contains machine code instructions. This file is a binary executable that the operating system can run.Shell Interaction: When you type

lsin the shell, the shell looks for thelsexecutable in directories specified by the PATH environment variable. If found, the shell runs the machine code instructions in thelsexecutable.

In summary, the shell doesn't interpret the C code directly. It relies on the compiled executable file to perform the desired functionality. The compilation step is what transforms the human-readable code into machine code that the computer's hardware can understand and execute.

😎 What about Directories in Linux , are those also an executable file ?

A directory in a file system is a special type of file that contains a mapping between filenames and the corresponding inode numbers. The inode is a data structure on a filesystem that stores information about a file or directory, such as its permissions, owner, size, and pointers to the actual data blocks on disk.

In the context of a typical Linux or Unix file system, directories are managed by the operating system kernel and are not typically written in C code by end-users. However, the implementation of directories and file systems, including their management and manipulation, is indeed written in programming languages like C or C++. The code is part of the operating system kernel or associated file system drivers.

Here is a simplified explanation of how directories work:

Directory Structure:

- A directory contains entries that associate filenames with inode numbers. Each entry in the directory points to an inode, which, in turn, points to the actual data blocks on disk.

Inodes:

- Inodes store metadata about files or directories, including information about the file's location on disk, permissions, owner, and timestamps.

Filesystem API:

- The operating system provides a filesystem API (Application Programming Interface) that allows programs (including those written in C) to interact with directories and files. This API includes functions for creating, reading, updating, and deleting files and directories.

File System Operations:

- When a user or a program requests an operation on a file or directory, the operating system translates these requests into low-level operations on the filesystem. For example, creating a file involves allocating an inode, updating the directory entry with the new filename and inode number, and initializing the file's data blocks.

Filesystem Drivers:

- Filesystem drivers, implemented in C or other programming languages, handle the details of interacting with specific types of file systems (e.g., ext4, XFS, FAT32). These drivers are responsible for translating high-level filesystem API calls into low-level operations specific to the underlying storage.

The details of directory implementations can vary between different filesystems, but the basic concepts are similar. Directories provide a hierarchical structure for organising files, and the operating system manages the mapping between filenames and inodes to facilitate file access and manipulation.

😫 Hold on ! What is Kernel and Where to see Inode?

Kernel :

Imagine your computer is like a magical kingdom, and the kernel is the wise and powerful king who makes sure everything in the kingdom runs smoothly.

The king (kernel) takes care of all the little tasks in the kingdom. For example:

He makes sure all the different programs and games (like knights and wizards) get their turn to use the computer.

He keeps track of where all the important things are stored, like your pictures and videos (in the castle library).

The king also talks to all the different devices, like the printer and the internet (sending messages to the messenger birds).

In short, the kernel is like the superhero king of the computer, making sure everything works well and everyone can do their jobs!

The term "kernel" refers to the core component of an operating system. It is the central part of the operating system that manages system resources, facilitates communication between hardware and software components, and provides essential services for various processes and applications.

The kernel acts as an intermediary between the computer's hardware and user-level applications. Its primary responsibilities include:

Process Management: The kernel manages processes, which are instances of executing programs. It handles process scheduling, creation, termination, and synchronization.

Memory Management: The kernel is responsible for managing the computer's memory. This includes allocating and deallocating memory for processes, implementing virtual memory, and handling memory protection.

Device Drivers: The kernel provides device drivers that allow the operating system to communicate with hardware devices such as disk drives, printers, and network interfaces.

File System Management: The kernel manages file systems, including handling file operations, maintaining file structures, and providing a uniform interface for file access.

Security and Access Control: The kernel enforces security policies and access controls to ensure that processes and users have appropriate permissions to access system resources.

System Calls: The kernel exposes a set of system calls, which are interfaces that allow user-level applications to request services from the kernel. Examples of system calls include file operations, process creation, and memory allocation.

Interprocess Communication (IPC): The kernel facilitates communication between different processes through mechanisms such as pipes, sockets, and shared memory.

The kernel is typically the first program loaded into memory when a computer boots up. It runs in a privileged mode, allowing it to execute critical operations that regular user-level processes cannot perform. Different operating systems have different kernel designs, and they can be classified into monolithic kernels, microkernels, and hybrid kernels based on their architecture.

Popular operating systems like Linux, Windows, and macOS all have their own kernels that play a crucial role in managing and coordinating the resources of the computer.

Inode :

Accessing and viewing the contents of an inode directly from user space is typically not a straightforward process. Inodes are managed by the operating system kernel, and direct access to them is abstracted by the file system API. In other words, you interact with files and directories through higher-level commands and system calls rather than directly examining the inodes.

However, you can use some command-line tools and utilities to gather information about inodes and file metadata. Here's a brief explanation:

lscommand: Thelscommand, when used with the-ioption, shows the inode number of files and directories in a directory:ls -istatcommand: Thestatcommand provides detailed information about a file, including its inode number:stat filenameReplace "filename" with the actual name of the file you want to inspect.

debugfstool:debugfsis a tool that allows you to interact with an ext2, ext3, or ext4 file system interactively. It's not recommended for casual use, as it provides low-level access to the file system. Use it with caution.Example:

debugfs -R "stat <inode_number>" /dev/sdXnReplace

<inode_number>with the actual inode number you want to inspect, and/dev/sdXnwith the appropriate block device and partition.

Now, regarding the internal structure of an inode, let's consider a hypothetical example:

Inode Number: 12345

File Type: Regular File

Permissions: 0644

Owner: User1 (UID 1001)

Group: Group1 (GID 1001)

File Size: 1024 bytes

Timestamps:

- Last Access: 2024-01-23 12:34:56

- Last Modification: 2024-01-23 12:34:56

- Last Status Change: 2024-01-23 12:34:56

Data Block Pointers:

- Direct Block 1: 5678

- Direct Block 2: 5679

- Indirect Block: 6789 (Points to blocks with more data block pointers)

- Double Indirect Block: 7890 (Points to blocks with indirect block pointers)

- Triple Indirect Block: 8901 (Points to blocks with double indirect block pointers)

This example illustrates some common attributes you might find in an inode. The data block pointers point to the actual locations on disk where the file's content is stored. The specifics can vary between file systems. The example provided here is a simplified representation for educational purposes. Always use dedicated tools and commands to access and manage file system metadata in a real environment.

Implementing a full-fledged inode and file system involves a substantial amount of code and is typically beyond the scope of a single response. Additionally, creating a file system from scratch is a complex task that requires careful consideration of many factors, including disk management, block allocation, and data structures.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

// Simplified Inode Structure

typedef struct {

int inode_number;

int size;

// Other metadata fields like permissions, timestamps, etc. could be added here

} Inode;

// Simplified File Structure

typedef struct {

char name[50];

Inode inode;

// Other data fields could be added here

} File;

// Function to create a new file

File createFile(char* name, int inodeNumber, int size) {

File file;

strcpy(file.name, name);

file.inode.inode_number = inodeNumber;

file.inode.size = size;

return file;

}

// Function to print file information

void printFileInfo(File file) {

printf("File Name: %s\n", file.name);

printf("Inode Number: %d\n", file.inode.inode_number);

printf("File Size: %d bytes\n", file.inode.size);

}

int main() {

// Create a sample file

File myFile = createFile("example.txt", 1, 1024);

// Print file information

printFileInfo(myFile);

return 0;

}

When an operating system starts up, it executes code that is written in languages like C or C++. This code includes various components of the operating system, such as the kernel, device drivers, and file system drivers. The file system driver, in particular, is responsible for managing the file system, interpreting file structures, and handling file-related operations.

While we commonly refer to these components as "code" or "programs," the term "script" is not commonly used in the context of the core operating system or its drivers. Instead, these are typically compiled programs or modules that are loaded into memory and executed as part of the operating system's startup process. The use of compiled languages like C or C++ provides efficiency and direct control over system resources.

So, to summarise, the operating system, including the file system functionality, is implemented in languages like C or C++, and the compiled code of these components is executed by the computer's hardware during the startup process.

🔐 What About Permissions on who can access specific Directories and Files ?

The "Who" ?

In Linux and Unix-like operating systems, file and directory permissions are organized into three categories: owner, group, and others. These categories determine who can perform specific actions on a file or directory.

Owner:

The owner is the user who owns the file or directory.

The owner permissions apply to the user who created the file or directory.

The owner can read, write, and execute the file (if it is an executable).

On Your Personal Device.

You are the owner of the files and directories you create and You have full control over the files, including read, write, and execute permissions.

Group:

Every user on a Linux system belongs to one or more groups.

The group permissions apply to users who belong to the same group as the file or directory.

The group owner of a file or directory can read, write, and execute the file (if it is an executable).

On Your Personal Device.

Your user account is typically associated with a primary group. By default, this group is often the same as your username. You are the only member of this group unless you explicitly add other users.

Others:

Others are users who are neither the owner nor part of the group associated with the file or directory.

The "others" permissions apply to all users who do not fall into the owner or group categories.

Others can read, write, and execute the file (if it is an executable).

On Your Personal Device.

"Others" refers to all users who are not the owner and not part of the group associated with the file or directory. On a personal laptop, if you are the sole user, there are no other users, and "others" do not have any specific relevance.

The permissions are represented by the characters r (read), w (write), and x (execute). These permissions are organized into three sets, each indicating the permissions for the owner, group, and others. The order of the sets is typically displayed as "owner-group-others."

For example, if the permissions are shown as "rw-r--r--":

The owner has read and write permissions.

The group has read-only permissions.

Others have read-only permissions.

Permissions can be modified using commands like chmod in Linux. For instance:

# Add execute permission for the owner

chmod u+x filename

# Remove write permission for others

chmod o-w filename

To change the ownership of a file or directory in a Unix-like operating system, you can use the chown command. The chown command allows you to change both the owner and the group owner of a file. Here is the basic syntax:

there are three basic types of permissions, and they apply to files and directories. These permissions determine what actions users can perform on a particular file or directory. The three types of permissions are:

sudo chown new_owner:new_group filename

The "Type" ?

Read (r):

For files: Allows a user to read the contents of the file.

For directories: Allows a user to list the contents of the directory.

Write (w):

For files: Allows a user to modify the contents of the file.

For directories: Allows a user to create, delete, or rename files within the directory.

Execute (x):

For files: Allows a user to execute the file if it is an executable program or script.

For directories: Allows a user to access files and subdirectories within the directory.

| Permission | Symbol | Numeric Value |

| Read | r | 4 |

| Write | w | 2 |

| Execute | x | 1 |

Now, each set of three permissions (for owner, group, and others) is represented by a three-digit octal (base-8) number. The numeric value is calculated by adding the values of the individual permissions.

| Permission String | Numeric Value |

--- | 0 |

--x | 1 |

-w- | 2 |

-wx | 3 |

r-- | 4 |

r-x | 5 |

rw- | 6 |

rwx | 7 |

For example:

rw-r--r--translates to644.rwxr-xr-xtranslates to755.--x--x--xtranslates to111.

You can use these numeric values with the chmod command to set permissions. For instance:

# Set read and write permissions for the owner, read-only for group and others

chmod 644 filename

Quick Start =)

Most Used commands.....

| Command | Description |

ls | List files and directories in the current directory |

pwd | Print the current working directory |

cd | Change directory |

cp | Copy files or directories |

mv | Move or rename files or directories |

rm | Remove files or directories |

mkdir | Create a new directory |

rmdir | Remove an empty directory |

touch | Create an empty file |

cat | Concatenate and display the contents of a file |

nano or vim | Text editors for creating or editing files |

grep | Search for a pattern in a file or stream of text |

chmod | Change file permissions |

chown | Change file owner and group |

ps | Display information about running processes |

kill | Terminate a process by process ID |

top | Display system information and current processes |

df | Display disk space usage |

du | Display file and directory space usage |

man | Display the manual for a command |

tar | Create or extract compressed archive files |

ssh | Connect to a remote server using SSH |

scp | Copy files between local and remote machines using SSH |

wget | Download files from the internet |

curl | Transfer data with URLs |

sudo | Execute a command with superuser privileges |

journalctl | Query and display messages from the journal |

systemctl | Control the systemd system and service manager |

ifconfig or ip | Display network configuration information |

ping | Test the reachability of a host on an IP network |

traceroute or tracepath | Trace the route packets take to a destination |

Thank-you!

I am glad you made it to the end of this article. I hope you got to learn something, if so please leave a Like which will encourage me for my upcoming write-ups.

Connect with me on Linkedin

Start your own blogs